The health of humans, animals and the environment they live in are inextricably linked. “One Health” is the multidisciplinary approach that investigates aspects of human, animal and environmental health all together, from different perspectives.

Although the concept is universally recognised and based on a well-developed theory, the practical application of One Health is still limited, especially in developing regions and humanitarian settings in the Global South. Nonetheless, it has enormous promise for tackling complex health problems, particularly in communities where livestock is vitally important. More resources are needed for One Health to become a reality for everyone.

A successful first symposium

Along with three renowned partners, Vétérinaires Sans Frontières Belgium organised a first symposium on 27 June to explain One Health in greater depth:

Along with three renowned partners, Vétérinaires Sans Frontières Belgium organised a first symposium on 27 June to explain One Health in greater depth:

- Katharina Kreppel, an epidemiologist at the Institute of Tropical Medicine in Antwerp, opened the conference with a presentation sketching what exactly the concept of One Health involves.

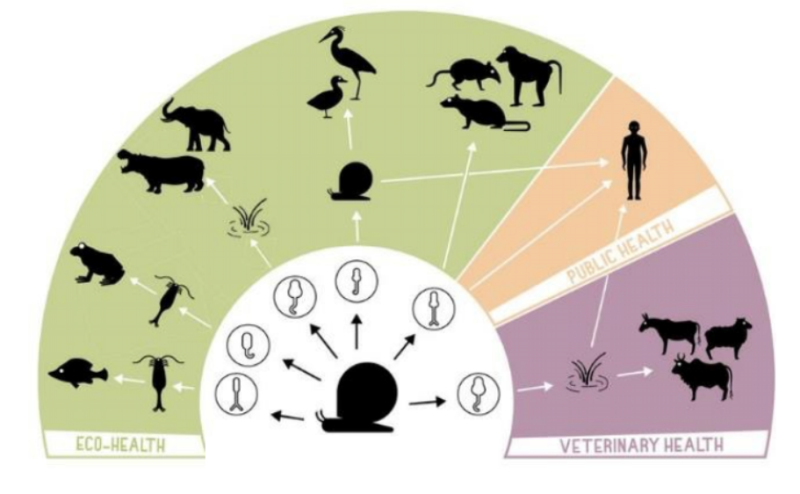

- Tine Huyse, a researcher in the biology department of the Royal Museum for Central Africa, followed with a presentation on the importance of the One Health approach in the fight against snail-borne diseases, such as schistosomiasis (bilharzia).

- Krizia Vieri, One Health Advisor at Médecins du Monde Belgium, with which Vétérinaires Sans Frontières Belgium carries out various projects, explained the importance of the community perspective in the practical applications of the concept.

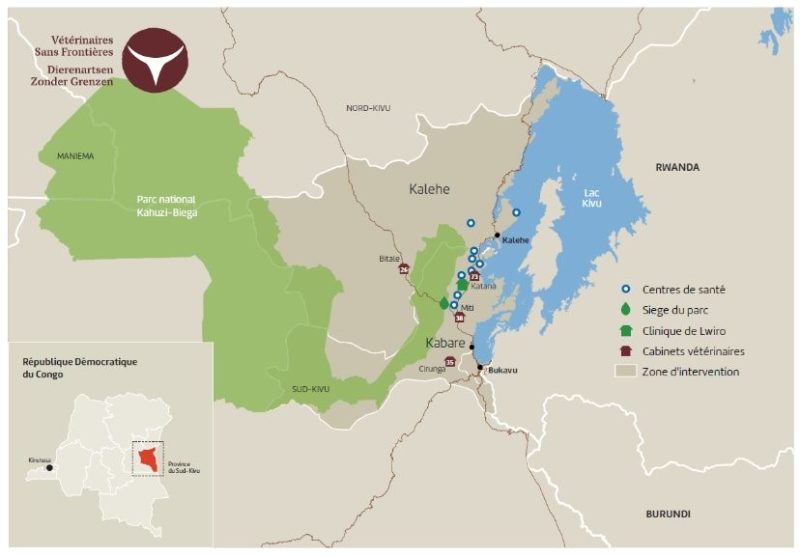

- Last but not least, our general director Joep van Mierlo offered an overview of the One Health pilot project developed by Vétérinaires Sans Frontières Belgium in partnership with Médecins du Monde Belgium and Action pour le Développement des Milieux Ruraux around Kahuzi-Biega National Park in South Kivu, DRC.

We hope to repeat this successful first experience to mark our 40th anniversary in 2025.

One Health, an approach with local communities in the lead

© Thomas Cytrynowicz

What distinguishes the One Health approach from concepts such as ‘planetary health’ and ‘eco-health’ is the principle that it is centred on its stakeholders. One Health goes beyond collaboration between sectors and disciplines: every layer of society is actively involved, from local communities to politicians at regional, national and international level. A crucial factor for the success of the One Health approach is listening carefully to local communities, which can often contribute valuable ideas, practices and solutions. Although this community-based approach requires more time and effort, it is considerably more sustainable than top-down methods that usually impose restrictions. Unfortunately, current policy often leads to the financing of rapid-response programmes that bypass local cultural customs and beliefs. However, a community-led approach can draw on a deeply embedded network of local social organisations, can reach even the remotest areas and is focused on capacity-building among local communities. Local NGOs play a vital role in this.

Challenges and opportunities illustrated by the case of diseases transmitted by snails

© Tine Huyse

A community-led One Health approach offers opportunities to integrate social civil society and local NGOs into the decision-making process for disease control programmes. For example, if we consider how snail-borne diseases are controlled, we see that considerable progress has already been made. Take schistosomiasis, for instance, a disease in which parasitic worms transmitted by snails affect both animals and humans. Good treatments are available, but there is no vaccine. Instead of only committing to treating the disease on a wide scale, however, a more successful approach has been to team up with the local population and commit to snail control and raising awareness of the risks of schistosomiasis, which include infertility. This has led to significant changes in behaviour, such as improved hygiene and avoidance of infected water.

Local communities can also play an important role in tackling environmental issues. A good example is Lake Kariba in Zimbabwe, where hippopotamuses are affected by parasitic liver flukes. Invasive water hyacinths are choking the lake and depleting nutrients and oxygen, which is having disastrous effects on the flora and fauna but also creates an ideal habitat for snails. This has led to increases in an exotic snail species that is more likely to be infected with liver flukes than the native species, thus creating health risks for the hippos. There is a great opportunity here for involving the local population in the fight against water hyacinths, as these plants can be put to excellent use as animal feed and organic fertiliser, as already proven in Senegal.

Instead of investing in short-term top-down interventions, a community-led approach results in more sustainable solutions. Involving local communities in citizen science initiatives has also led to better monitoring of snail populations and the mapping of hazardous areas and high-risk practices. As a result, local communities are increasingly able to protect themselves from the risks of infection.

One Health in practice

In the eastern DRC, we are actively applying the One Health approach in order to prevent zoonotic disease outbreaks in and around Kahuzi-Biega National Park. This area has a high risk of zoonotic disease transmission, because the local communities here live in close contact with animals and nature. With more than 75% of the population living below the poverty line, many turn to illegal logging and poaching for their livelihoods. Doing so, they expose them unwittingly to diseases with epidemic potential, such as Ebola and Covid-19.

In the eastern DRC, we are actively applying the One Health approach in order to prevent zoonotic disease outbreaks in and around Kahuzi-Biega National Park. This area has a high risk of zoonotic disease transmission, because the local communities here live in close contact with animals and nature. With more than 75% of the population living below the poverty line, many turn to illegal logging and poaching for their livelihoods. Doing so, they expose them unwittingly to diseases with epidemic potential, such as Ebola and Covid-19.

Our goal with the One Health project is to prevent infectious disease outbreaks, detect them early and get them under control quickly. To do this, we have set up four veterinary practices near the national park and trained 172 community animal health workers, who are responsible for epidemiological surveillance and awareness raising within their communities. With our local partner Action pour le Développement des Milieux Ruraux we work on restoring the ecosystem. All the stakeholders are also brought together in umbrella consultation platforms, where doctors, vets and environmental experts regularly consult each other and form the basis of an integrated epidemiological surveillance system.

© Thomas Cytrynowicz

At the initiative of Doctors of the World Belgium, we are conducting participatory action research with local community leaders from 13 villages, representatives of the indigenous population, the police, representatives from the agricultural sector, etc. This research has identified high-risk practices, such as the consumption of raw meat and dead animals, and the close contact between livestock and humans. Based on these findings, we are sensitising the communities about the risks, and together we draw up a shared plan with specific, feasible actions to put a stop to high-risk practices in order to prevent the emergence of zoonoses and environmental damage. By committing to a participatory approach, we hope to give local people themselves control over their own health, while respecting their cultural traditions and preserving their environment.

This project is being implemented by Vétérinaires Sans Frontières, Doctors of the World Belgium and Action pour le Développement des Milieux Ruraux, three NGOs specialised in human, animal and environmental health.