Why does this construction approach fail? Latrine construction focusses on a possible solution, not on the problem. The problem is the spread of waterborne diseases such as diarrhoea and hepatitis, which is partially caused by unhealthy sanitation practices. That is where the CLTS-approach comes in. CLTS? Yes, the development sector has so many abbreviations that sometimes the local Ngakarimajong seems to be an easier language to learn. CLTS stands for Community-Led Total Sanitation approach. It aims at achieving a sustainable behaviour change; to stop open defecation (OD). The lead is taken by the community, who develops its own action plan. Sounds great. But how does it work in practice?

There are 7 main tools, which are used to trigger the community. After gathering the community in the shade of a tree for a short introduction, the action starts. The community is asked to draw a plan of their village by using stones, branches or whatever local material is easily available. Besides drawing the manyattas (grouped households), they also indicate water sources and the places where they defecate. It can be some bushes next to the manyatta, in the field, or just behind the kitchen. The places that they identified for open defecation, is where we all go next, looking for fresh poo-poo, on “The Walk of Shame”. Once the community finds a nice fresh shit –and yes, let us call a spade a spade- they pick it up and walk around the village with it. Everyone carries it, preferably the village leader first. As expected, this creates a lot of reactions: disgust, disbelief, laughter… As a participant, you immediately feel that the community is excited and interested in what this is all about.

The other tools are mainly to let the community acquire insight in the relation between open defecation and their health. A clean bottle of water is passed around, and people drink from it. Then, a community member takes a little branch or anything what is available, takes a bit of the poo-poo, and puts it in a new bottle of clean water. After shaking, the water seems clear again, but no-one wants to drink from it anymore. Why not? Because after all, if it rains, faeces are also ending up in their rivers, from which they sometimes drink. So, what is the difference?

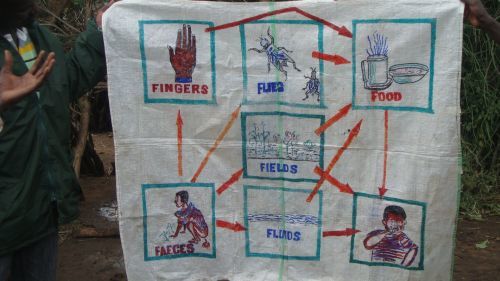

Then there is the shit calculation (how much bags of shit produced in one year by one village? Where do they end up, because we don’t see them?), the flow-diagram (how do you end up “eating faeces”?) and calculation of medical expenses due to sanitation related diseases. Mostly, the community gets rather astonished by all this, and wants to take action. If they feel like taking action, they draw themselves an action plan and identify natural leaders to follow-up on the plan.

The actions undertaken are to obtain an “OD-free” community. This doesn’t necessarily involve latrine construction, because this is often not feasible for a small poor community. If that would be the initial aim, it would quickly discourage. On sanitation, you can start small. Maybe you start by picking one spot where everyone goes for a call of nature. This can then be scaled up to digging small pits which you cover up, the so-called “cat method”. And then you scale up again and again. Until there are latrines, constructed with local materials by the future users. Latrines which will not be used as the local leader’s office.

I admit, I first thought this sounded first as a weird approach. Shaming people with their shit? Isn’t it a bit arrogant of us? Who are we to tell them to go on a walk of shame? But we got the help of the WASH experts of PROTOS on this. And they have tried many things on sanitation and they experienced that this is the most effective thus far. Also other NGOs in the region tell us about the positive change they are experiencing. We have now piloted the CLTS-approach in 4 villages. Together with the local government we are following them closely. And we do see the first signs of progress. I am curious what the results will be…

Karolien Burvenich